What are we saying to males told to “man up” or to “act like a man”?

Date: Thursday 31 Aug 2017

My first home was a house called Slieve Moyne in the village of Woodhall Spa, in Lincolnshire. In later years I would think of the place as Tatooine, the planet Luke Skywalker imagines to be furthest from the bright centre of the universe. But for now, it was the universe and one with which I was perfectly content. There was just one problem. When we first meet Luke on Tatooine, he has an issue with his mysteriously absent father. My father, on the other hand, was all too present. And his name might as well have been Darth Vader. Actually it was Paul. It’s a silly comparison of course. Dark Lords of the Sith aren’t constantly wasted.

It’s the mid-1970s and I live with Mum, Darth Vader and my two older brothers, Mark and Andrew.

''I like it here. There are no men, and there are no other boys. I don’t seem to be very good at being a boy and I’m afraid of men.One man in particular.''

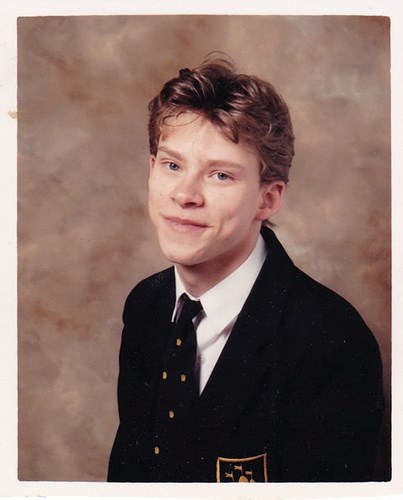

In this extract from his new memoir, the comedian and actor revisits a village childhood overshadowed by the violent temper of his father and the premature death of his mother.

imagine a child’s drawing of a house. This one would show three bedrooms upstairs, the little one with Rupert the Bear wallpaper for me, the middle one for the grownups and the one at the other end containing Mark and Andrew wearing denim waistcoats and walloping each other with skateboards (because that’s what Big Brothers do). holding double pages of the Daily Mail against the fireplace to encourage the flames. Sometimes he gets distracted while doing this because he’s shouting at James Callaghan on TV, and the paper catches fire. He has to throw the lot into the fireplace, which, of course, sets fire to the chimney.

He has laid the fire using the logs and sticks that he chopped up with the chainsaw left leaning against the back door, the one he uses for his job as a woodsman on the local estate (my Daddy is a woodcutter). The Mummy will be in the tiny kitchen, standing over an electric hob (because that’s what Mummies do) and stirring Burdall’s Gravy Salt into a saucepan of brown liquid.

If it has to come out at all, let it come out as anger. You’re allowed that. It’s boyish and man-like to be angry

It’s a static picture, of course, so we can’t see that the Mummy’s hands are shaking because she knows that the Daddy has spent all afternoon in the pub and has come home in one of his “tempers” (because that’s what Daddies do). If, during tea, one of the Big Brothers speaks with his mouth full or puts his elbows on the table, the Daddy has been known to knock him clean off his chair. The Mummy will start shouting at the Daddy about this but, of course, she can’t shout as loud as the Daddy. No one can shout as loud as the Daddy or is as strong as the Daddy, which is why the Daddy is in charge. The Little Brother will start crying at this point and will most likely be told to shut up by the Big Brothers who are themselves trying not to cry because that’s another thing that they’ve learned doesn’t go down well with the Daddy.

I remember the summer’s day when I was watching the Six Million Dollar Man battling with Sasquatch and the following moment I was being lifted an impossible number of feet into the air and thrashed several times around the legs with a pair of my own shorts that had been found conveniently nearby. Dropped back on the settee, I looked at those navy-blue shorts with a baffled sense of betrayal. They were my shorts. My navy-blue shorts with the picture of Woody Woodpecker on the pocket. And he’s just hit me with them. Maybe in the seconds before I was watching Steve Austin, I’d spilt something or broken something. Maybe I’d got too close to the fire or the chainsaw. Who knows? Actually telling a child why he was being physically punished was somehow beneath the dignity of Paul’s parenting style.

There are happy early memories from Slieve Moyne too, of course. Singing along with Mum whenever her beloved Berni Flint appeared on Opportunity Knocks; the thrilling day the household acquired its first Continental Quilt (a duvet), which my brothers and I immediately used as a fabric toboggan to slide down the purple stairs; playing in the snow, playing in the garden – all the sunlit childhood fun you’d expect from times when Dad was out.

Best of all was sitting on the back seat of the car, Mum driving us between the golf club where my grandparents (and Auntie Trudy) work in the kitchen and our new bungalow in the next village. It’s a journey we made many times a week and the tap of her wedding ring on the gearstick is one of the happiest sounds of childhood. It means that I’m alone with Mum.

“Quiet boy”, “painfully shy”, “you never know he’s there”: these are some of the phrases I catch grownups using when they talk about me. But not here, not in the car with Mum. And definitely not when Sailing by Rod Stewart comes crackling over the MW radio. The gusto of our sing-a-long is matched only by the cheerful lousiness of my mother’s driving.

I like it here. There are no men, and there are no other boys. I don’t seem to be very good at being a boy and I’m afraid of men.

One man in particular.

To be fair, there were moments when he was affectionate. For example, if he was in a good mood he might crouch down in front of me, put his massive fist under my nose and say in a joke-threatening way, “Smell that and tremble, boy!” For years I wasn’t quite sure what this phrase meant – “smellthatandtremble” – it was just a friendly noise that my dad made when he was trying to make me laugh. Oh, and I laughed all right. I mean, you would, wouldn’t you?

But in general, I’m afraid my memories of those first five years in that house tend towards the nature of a bad dream. To avoid real bad dreams, the trick was to make sure there was a gap in my bedroom curtains where the light could come in. But the real problem was not avoiding the night-time imaginings but the daytime reality. Not the Phantom, but the Menace. And he was unavoidable.

A classic of this sci-fi/horror genre was the episode called “Do an eight, do a two”. This family favourite has me, aged five, sat in the living room with a pencil and paper, being yelled at by Dad to “DO AN EIGHT! DO A TWO!” It had come to his attention that I wasn’t doing very well in my first year at primary school and that, in particular, I was unable to write the numbers 8 or 2. Actually, I could write an 8, but I did it by drawing two circles, a habit which Mrs Morse of St Andrew’s Church of England Primary School found to be lacking calligraphic rigour. Anyway, the rough transcript of “Do an eight, do a two” goes like this:

Dad: DO AN EIGHT! DO A TWO!

Mum: He’s trying! There’s no point shouting!

Dad: JUST DO AN EIGHT!

(Five-year-old, sobbing, does an eight with two circles)

Dad: NOT LIKE THAT! DO A PROPER ONE!

(Five-year-old dribbles snot on to the paper and does some kind of weird triangle)

Dad: WHAT’S THAT MEANT TO BE? DO AN EIGHT!

Mark: Or a two!

(Eleven-year-old Mark, desperate for any rare sign of approval from Dad, has joined in)

Dad: WHY CAN’T YOU DO ONE? JUST DO AN EIGHT!

Mark: Or a two if you like, Robbie! Why not do a two, probably?

(Mum takes five-year-old on her lap. Five-year-old thinks it’s over)

(Comedy pause, titters from the studio audience)

Mum: Try and do a two, darling.

(Five-year-old freaks out. Then somehow manages a wobbly two)

Dad: DO A TWO!

Mum: HE’S DONE A BLOODY TWO!

Dad: DO ANOTHER ONE!

Mark: Or an eight!

You might be thinking “this is nothing” compared to your own experiences with a domestic hardcase. Or maybe you’re wondering how my mother put up with it for an instant. The truth is, we were all terribly afraid of him. In any case, Mum was probably just biding her time at that point. She had already made her plans. Before the end of that first school year, she divorced him and he moved out.

I started keeping a diary after my 17th birthday. Early in March 1990 I wrote:

“My concern for Mum deepens. I’m quite ashamed to realise that this is the first reference in this diary to worrying about anyone but myself. Mum has been in hospital since last Friday with what was supposed to be a chest infection. In fact she has a few cancerous cells on her lung. She might have to have chemotherapy. Jesus Christ I’m so worried – I love her so much. I must resolve to be less selfish, to talk to her about things more often. Life without her is unthinkable. Literally unthinkable.”

And then, at the end of an entry a few weeks later:

“Found out for sure, the week before last, on Wednesday March 21st, that Mum definitely isn’t going to recover. She has about four months. I don’t want to talk about it. Even to you.”

That day, I had arrived home from school and felt a sudden tightness in my chest. Dad’s van was parked neatly outside the bungalow.

Dad is at the kitchen table with Derek, Mum’s second husband. He starts talking and the world ends.

“Y’mum’s poorly, boy. It’s terminal.”

You can get quite a lot of juice out of that word “terminal”, if you speak with a Lincolnshire accent and are quite drunk. The way he says it, the “er” sound is dug from the very depths of his diaphragm.

I look across at Derek, who is leaning an elbow on the table with a hand covering his mouth. He nods a tiny confirmation. Incredibly, somewhere in the room, Dad is still talking. “It’s ’orrible, boy, but that’s life. Now, I don’t know if you want to come and live with me or … ” he looks around the kitchen, “I mean, you’re probably going to need a cleaner, Derek, because … well, it’s hard keeping a place clean.” Derek nods. “Josie, who cleans my house, she could probably come and do a couple of hours a week.”

Derek says, “What does she charge, like?”

“Well, I give her a fiver, mate.” Derek is alarmed by the prospect of paying Josie £5 and he’s about to haggle, but stops because he’s noticed I’m crying.

“I know, boy,” Dad says, “it’s ’orrible.”

Here I am then, with Mum about to vanish, stuck here in the kitchen with the Idiot Brothers talking about Dad’s cleaner.

When Dad leaves, I notice that on the side of the van is painted the name of his business, which today looks less like an advertisement than like a rare flash of self-awareness: Paul Webb, Ltd.

I’m next to Mum on her bed, later that day. With effort, she draws herself up on her stack of pillows. “I’m sorry, darling, that wasn’t a very nice way to find out. I should have told you myself.”

I make an ineffectual gesture to help with the pillows but I’m scared of getting in her way. She’s got Dallas on the portable telly with the sound turned low. Bobby Ewing is having a long meeting with assorted oil barons.

She says, “Now then, is there anything you want to ask me? Or is there anything you want to say to me?” I feel a thousand future selves lean in to listen with interest. I rack my brain: there is no question up to the task and no statement either, apart from “I love you”, but I don’t trust myself to say that without losing it. I don’t want to do that; I’m her son and I want to be strong. So I say the thing that bothers me most about being 17 and me.

“I suppose … I mean, this isn’t important.”

“Go on … ”

“I’m a virgin.”

She starts to smile, but doesn’t want to look like she’s taking the piss. Also, smiling takes effort and she’s working hard to talk. She says, “I won’t say I’m surprised; I won’t say I’m not surprised. But you’ll catch up.”

“All my mates have got girlfriends.”

“You’ll overtake them. In everything.”

This emboldens me, so I try a promise. “I’m going to get three As and go to Cambridge, Mum.”

She’s ready for this one. “I know you’ll be happy wherever you end up, Rob. I’m proud of you already, so don’t worry.”

**************

What are we saying to a boy told to “man up” or to “act like a man”?

Often, we’re saying, “Stop expressing those feelings.” And if a boy hears that enough, it actually starts to sound uncannily like, “Stop feeling those feelings.”

It sounds like this: “Pain, guilt, grief, fear, anxiety: these are not appropriate emotions for a boy because they will be unacceptable emotions for a man. Your feelings will become someone else’s problem – your mother’s problem, your girlfriend’s problem, your wife’s problem. If it has to come out at all, let it come out as anger. You’re allowed to be angry. It’s boyish and man-like to be angry.”

**************

Read more HERE