Why coronavirus highlights the need for targeted support for male mental health

Date: Tuesday 07 Jul 2020

Unemployment and social isolation, combined with ingrained ideas about masculinity, can cause difficulties for men.

From: The New Statesman

Lockdown has had an impact on the mental health and wellbeing of many people, but, say experts, there are specific problems affecting men, leading to calls for more specialised support.

“It is critical that the government puts suicide prevention at the heart of its coronavirus recovery strategy, with financial support for less well off men being key”, says Joe Potter, a policy manager for The Samaritans.

''With many charities struggling for funding at the moment, especially smaller ones, community-based support services that target male mental health need government support to innovate and expand their digital and physical outreach'', adds Potter.

The UK-based charity, Global Action on Men’s Health, is advocating for more gender-responsive health promotion work, more specifically, mental health communication and services that are better designed to the specific needs of men and women .“Men’s mental health is highly likely to be more affected than it might at first sight appear,” says Peter Baker, the charity’s director.

“For men, what we need is communications through mainstream media and social media which address some of these mental health issues.”

A report from Mind and the Mental Health Forum says that there is evidence that messages that draw on “traditional” male sensibilities (such as “having the courage” to act) may be effective, thereby helping to change some men’s perception that taking care of their mental health is “unmasculine”.

A survey from Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) found similar conclusions, with 82 per cent of its male respondents saying they wanted to be the person that was there for their friends, and the person who is asked for help.

“Men want to be there to help each other, and our kind of campaigning is to encourage acknowledgement of these facts and help [men do that for each other], whether that is through football, comedy, music or whatever,” says Simon Gunning, CEO of CALM, a charity that supports the prevention of male suicide.

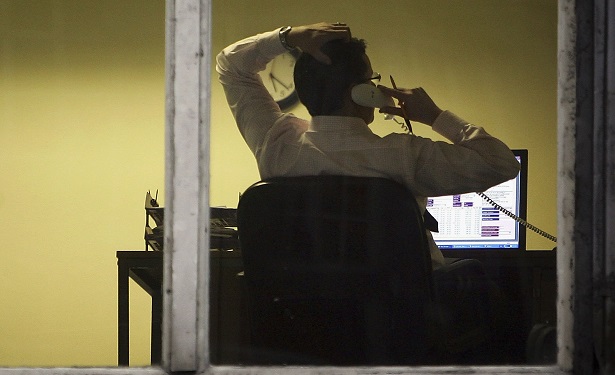

Peter Baker also acknowledges that traditional notions of masculinity also have an impact on male mental health. “We know that work is a central part of male identity. The loss of it is creating a lot of anxiety and stress in many men, [who] tend to be more reluctant to talk''.

“[Lockdown] also means a loss of workplace camaraderie and other activities where men have social contacts. Men tend to be more isolated than women and have smaller social networks,” adds Baker.

The majority (60 per cent) of people living alone in the UK between the ages of 25 to 64 are men, according to pre-lockdown ONS data. This is even more pronounced for younger men within this age group.

The strain of living under lockdown is putting people at higher risk of suicide. Suicide is the single biggest killer of men under the age of 45, and in recent years, roughly 75 per cent of all suicides in the UK were undertaken by male individuals, according to the Office of National Statistics (ONS).

“If you’re a young man in Britain, the most likely thing to kill you, is you,” says Gunning.

The correlation between economic recession and increased suicide rates amongst men is also very close, as seen during and after the 2008 financial crisis.

Less affluent middle-aged men have remained the highest risk group for suicide in the UK for decades, according to the Samaritans. Lockdown will be increasing isolation and disconnection for many of these men, exacerbating problems, says Potter.

CALM has witnessed a 37 per cent increase in people using its helpline since the start of lockdown, with the vast majority of its callers being men, says Gunning. “What I think we’ll see [once] the evidence is available, is an increase in suicide rates in men, and that will be a tip of the iceberg in terms of what’s been going on with men’s mental health generally.”

Conversely, being stuck at home with family or a partner can also be a driver of poor mental health and relationship problems for men. “Home is not somewhere where many men are used to spending lots of time. There may be an expectation of having to play a greater role in domestic life. Some may see that as a threat to their identity, or simply feel like they lack the skills to do that properly,” says Baker.

Sebastian Shehadi is the political editor (FDI) at NS Media Group. Laure-Anais Zultak is a global health policy consultant